Study Turns Conventional Thinking on Myofascial Back Pain Upside Down

By Victoria Rea

15 July 2021

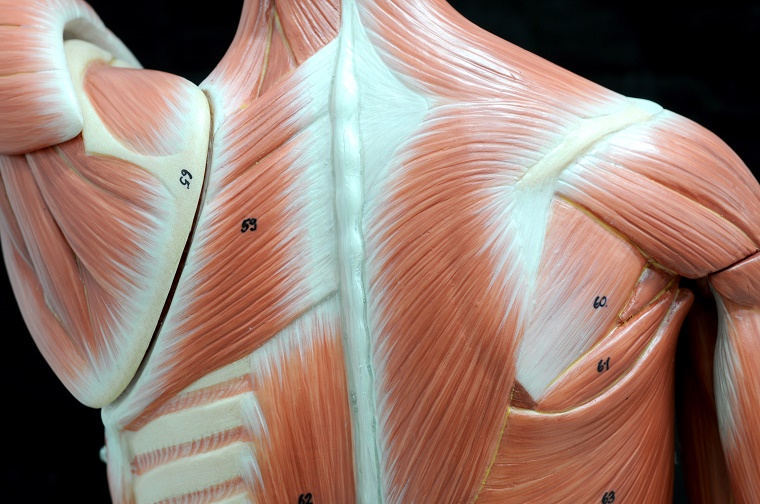

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is something most people have experienced. People suffering from chronic pain often have tight and tender knots in their skeletal muscle, also known as myofascial trigger points, that commonly occur in the neck and back.

Myofascial trigger points are typically treated as a symptom of muscle injury by chiropractors and other doctors. But one researcher at the University of Guelph believes that we may be looking at the cause of myofascial pain all wrong.

Dr. John Srbely is an associate professor in the Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences who started his career as a chiropractor and acupuncturist in 1992. The focus of his practice for over 25 years was treating patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and myofascial trigger points.

Like most clinicians, he centered his treatment on the belief that the myofascial trigger point was caused by a local injury within the affected muscle. But he quickly discovered that this was not always a reliable approach.

“In a lot of my patients, I had a hard time identifying injury associated with their trigger points in their clinical history,” says Srbely. “Furthermore, when treating trigger points with manual therapy or dry needle therapy, patients described the pain as ‘good pain’, often inviting deep pressure.”

“These observations were counterintuitive to a local injury mechanism and, based on these clinical observations, I began questioning the prevailing wisdom that local injury is the source of this type of pain.”

This set Srbely on a path to study a phenomenon called central sensitization. Central sensitization is a response of the central nervous system to ongoing pain from a particular tissue that makes the nerves highly reactive and triggers neurogenic inflammation. This in turn leads to the release of neuropeptides that cause hypersensitivity elsewhere in the body.

This topic is now a major focus of Srbely’s lab, which recently published a paper providing the first direct evidence of a cause and effect relationship between osteoarthritis in the spine and inflammation in muscle tissue.

In a study led by recent PhD student Felipe Duarte, the researchers surgically induced spine arthritis in rats and then examined changes in the levels of inflammatory biomarkers within neurologically connected muscles. Compared to control rats that underwent a mock surgery only, rats with induced spine arthritis had higher levels of the biomarkers.

Importantly, the study showed that the high levels of inflammatory biomarkers were found specifically in muscles supplied by nerves connected to the part of the spine where the arthritis was induced, but not in muscles supplied by nerves connected to other parts of the spine.

Not only that, but the rats with arthritis were also more sensitive to heat and touch, providing further evidence that the process of central sensitization was at play.

Overall, the results draw a direct connection between the spine arthritis and muscle inflammation.

This research is especially important given our rapidly growing aging population, where both osteoarthritis and chronic myofascial pain is highly prevalent.

“This model actually explains a lot of clinical observations, such as chronic myofascial pain in the absence of injury that we observe in older individuals,” says Srbely.

Srbely’s group has previously shown associations between age-related spine degeneration and inflammatory response in geriatric rats, but this is the first time direct causation has been demonstrated via experimentally induced spine osteoarthritis.

Srbely hopes this work will improve how we diagnose and treat patients with chronic back pain.

“Clinicians have traditionally treated the trigger point under the assumption that it is the primary pathology in chronic myofascial pain. But the Neurogenic Hypothesis we are proposing suggests that the primary pathology does not actually reside within the muscle itself. The trigger point is now a secondary response. It’s not the cause, it’s an effect. It’s very possible that we have been looking in the wrong places up until now.”

This study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Read the full study in the journal Experimental Gerontology.

Read about other CBS Research Highlights.