Bold is Best: How Personality Impacts Mating and Chick Survival in Arctic Seabirds

By Bailey Bingham

7 January 2020

It is an age-old question for all lovelorn creatures: what personality traits are most important when picking a partner? Researchers from the Department of Integrative Biology have finally found the answer – at least for one species of Arctic seabird. Undergraduate researcher Sydney Collins and a team of colleagues led by Prof. Shoshanah Jacobs have found that boldness is not only important to mate selection in Black-legged kittiwakes, but also to chick survival.

“Traditionally in science, we assume that all individuals in a population will behave in the exact same way, but that just isn’t true!” says Collins. “ Individual animals vary in their behaviour, and these differences in personality can have major implications for reproductive success.”

During her undergraduate degree, Collins spent two summers in Middleton Island, Alaska studying how the personality trait of boldness was related to mate choice and reproductive success or “fitness” in Black-legged kittiwakes.

“There is often push back against the idea that non-human animals have personality, but you really just need to consider your pets to see that it exists,” says Collins.

Boldness – or an animal’s propensity for risk taking – is one personality trait that may be very important to fitness. It is typically measured by examining an individual’s response to a novel object.

Collin’s approach to measuring boldness required an innovative list of materials, including a retired radio tower turned seabird nesting site, one-way glass, a camera, and a stick with a ball of bright green duct tape at one end.

“I was essentially poking birds with sticks for science,” Collins says of her methodology.

With a pair of birds nesting on one side of the one-way glass, Collins and her team would poke a stick through a hole in the glass. Then the researchers recorded the bird’s reaction to the novel object and scored it on a shy-bold continuum that ranged from extreme fear to extreme aggression. They measured boldness in 24 mated pairs of birds several times throughout the breeding season, which allowed them to look at boldness over time.

The team found that both bold birds and shy birds tended to pick bold mates.

“Essentially, everybody wants a bold mate!” says Collins.

This preferential mating is likely due to the benefits that parental boldness has on chick survival. In fact, the researchers found that for every “unit” increase on the shy-bold scale for the shyest mate, chicks lived 6.5 days longer.

Nor was a bird’s boldness a static trait: both parents tended to display the greatest boldness when their chicks were hatchlings and most vulnerable to predators and in need of a parent in the nest to keep them warm.

The study highlights the importance of personality differences to wildlife conservation. With traits such as boldness having such a huge consequence on fitness, notes Collins, these differences should not be overlooked in developing conservation tactics.

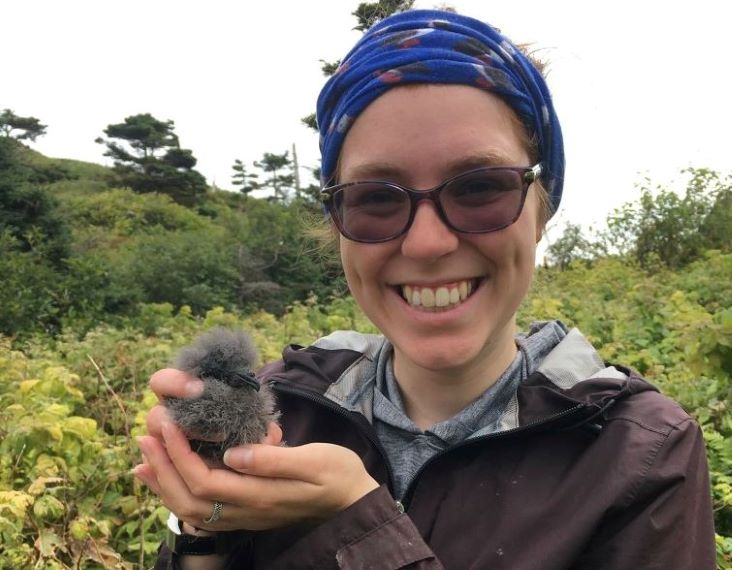

Now pursuing an MSc degree at Memorial University in Newfoundland, Collins is excited to learn more about animal personality and how it can factor into the conservation of vulnerable breeding seabirds. But these days, she has moved on from poking kittiwakes with sticks. “Now I am studying Leach’s storm petrels, and instead of poking them with sticks, I’m just using my finger!”.

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and the Northern Scientific Training Program.

Read the full study in the journal of Animal Behaviour.

Read about other CBS Research Highlights.